Rules and books of etiquette have played a part in American life and letters since our country’s colonial days.

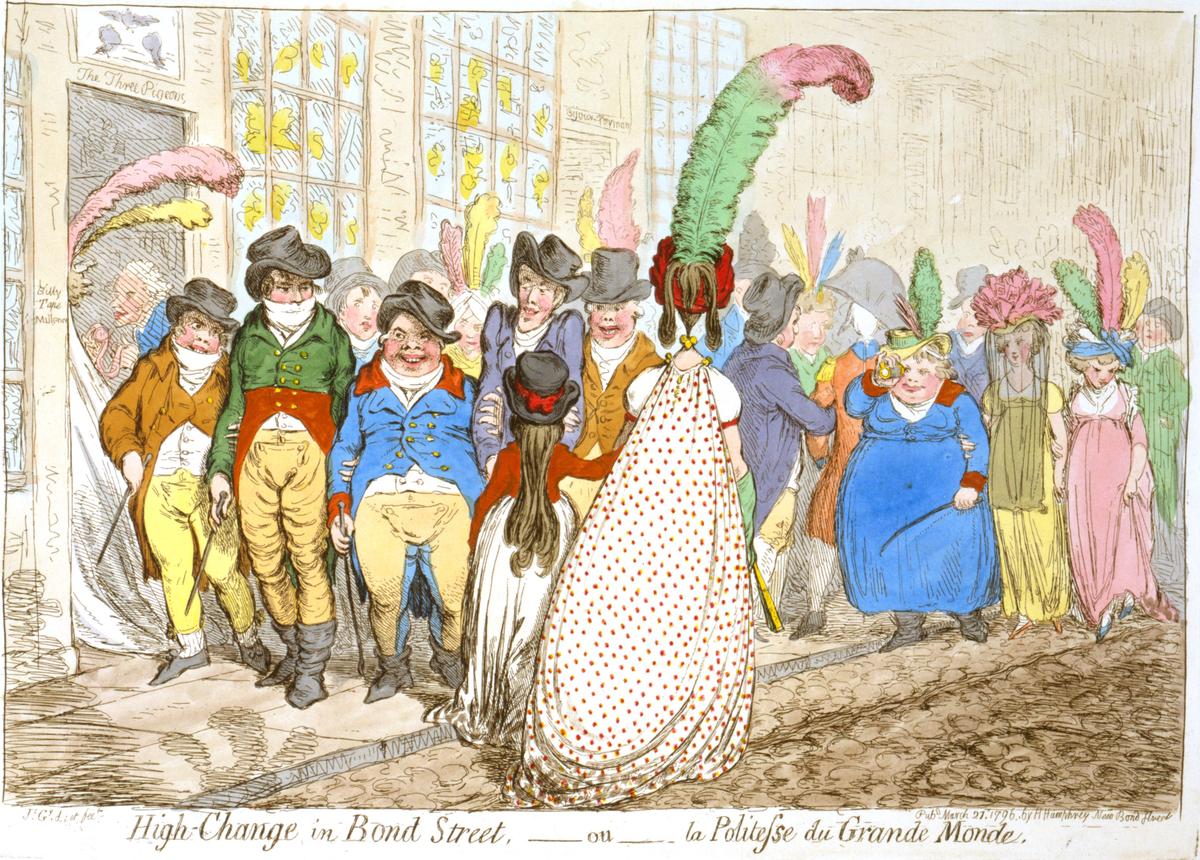

The large number of etiquette books published between the Civil War and the early years of the 20th century give us a sense of the public’s hunger for such guides. Before exploring some of these manuals, however, we need to remember that these handbooks pertaining to manners and conduct do not necessarily reflect contemporary behavior, but were instead instructions as to how men, women, and children should behave.

A Sparkling Array of Resources

A great blessing of our digital age is the enormous library available to us through the touch of a laptop key. One online compilation of 19th- and early 20th-century works about decorum and behavior, for example, features more than 50 books, most of which would otherwise be accessible only to a few scholars in a university library.

If we explore some of these books, and if we keep in mind that they are aspirational literature, we can with a few clicks on a keyboard time-travel back a century or more to our American past. If we look, for instance, at Washington’s “Rules,” we encounter reminders like this admonition: “Spit not in the Fire.” In other manuals, we’ll also find all sorts of instructions on how to deal with household cooks and maids. These observations may bring a smile, but they also provide a telescope into life as experienced by some of our predecessors.

“Never pick up anything that even your companion may drop, unless he should be very drunk. You may pick him up also, if he should drop.”

“Never, even if in haste, rush through a crowded thoroughfare at a breakneck gait, with your hair flying, your necktie over your ears, and shouting ‘Clear the track!’ at every jump. Hire a cab, or obtain roller-skates. Repose of manner should never be sacrificed to emotional insanity.”

The Mysterious Miss Hartley

In 1860, two popular manner guides appeared whose author remains shrouded in mystery: “The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette, and Manual of Politeness” and “The Gentlemen’s Book of Etiquette, and Manual of Politeness.” Florence Hartley wrote the first, Cecil B. Hartley the second, and we know today that they were one and the same person. Other books also appeared under these authors’ names: biographies of famous Americans like Daniel Boone and an instruction guide on stitchery and needlework.

Yet that’s about all we know. Other than the fact that Hartley apparently never married, no details of the author’s life—the dates of her birth and death, the places she may have lived—have come down to us. Her history is a blank sheet. Other writers of the mid-19th century, male and female, especially those who had written several books, were known to their audience. Was Hartley deliberately concealing her identity under a pen name for propriety’s sake, as some female authors of that period were wont to do? And how is it that she managed to publish two large tomes of manners in the same year?

Whatever the case regarding Florence and Cecil, these two books stand out today for the clarity of their language and for some general rules of etiquette that seem as fresh as the day they were written.

Hartley’s Introduction to her etiquette guide for ladies demonstrates both of these points. Consider this passage:

‘Though Much Is Taken, Much Abides’

Lord Tennyson’s words, cited above from his poem “Ulysses,” certainly apply to etiquette, as may be seen in Hartley’s two books. In her guide for ladies, she devotes most of the book to such dated topics as fancy dress, behavior at evening parties and balls, morning receptions—calling cards were de rigueur—and old-fashioned bridal etiquette.Readers today who are interested in these subjects, particularly as seen through the eyes of the mid-19th century, will find some treasures here. Hartley even includes a chapter on hints for good health and another on receipts, or recipes, for beauty and complexion.

In her chapter titled “Miscellaneous,” however, she offers some quick bits of general advice that might apply directly to our conduct today. For instance, she brings a social tactic often employed but seldom condemned:

“Many persons, whose tongues never utter a scandalous word, will, by a significant glance, a shrug of the shoulders, a sneer, or curl of the lip, really make more mischief, and suggest harder thoughts than if they used the severest language. This is utterly detestable. If you have your tongue under perfect control, you can also control your looks, and you are cowardly, contemptible, and wicked, when you encourage and countenance slander by a look or gesture.”

Into the Future

Published in 1922, Emily Post’s “Etiquette” became an instant bestseller and is now considered an American classic. A century later, Post remains the doyenne of American etiquette, and her descendants have preserved and continued her work through the Emily Post Institute, modernizing her ideas and adding to them.

And like Hartley, Emily Post herself recognized that etiquette is not so much about rules and prohibitions but a mixture of kindness, consideration, and ethics. She wrote: “Best Society is not a fellowship of the wealthy, nor does it seek to exclude those who are not of exalted birth; but it is an association of gentlefolk, of which good form in speech, charm of manner, knowledge of the social amenities, and instinctive consideration for the feelings of others, are the credentials by which society the world over recognizes its chosen members.”

Yet nearly all of us can still distinguish between the well-behaved and the rude—those who endeavor to make us feel warm and welcome as sunshine and those who could bring a frost to a July afternoon. Men may no longer practice the custom of tipping their hats to ladies, but we recognize consideration and manners when we encounter them.

Reading some Florence Hartley or, for that matter, Emily Post can be both educational and entertaining. But most of all, these authors and many more remind us that treating others—family, friends, strangers—with respect and politeness is a key linchpin in the workings of a civilization.