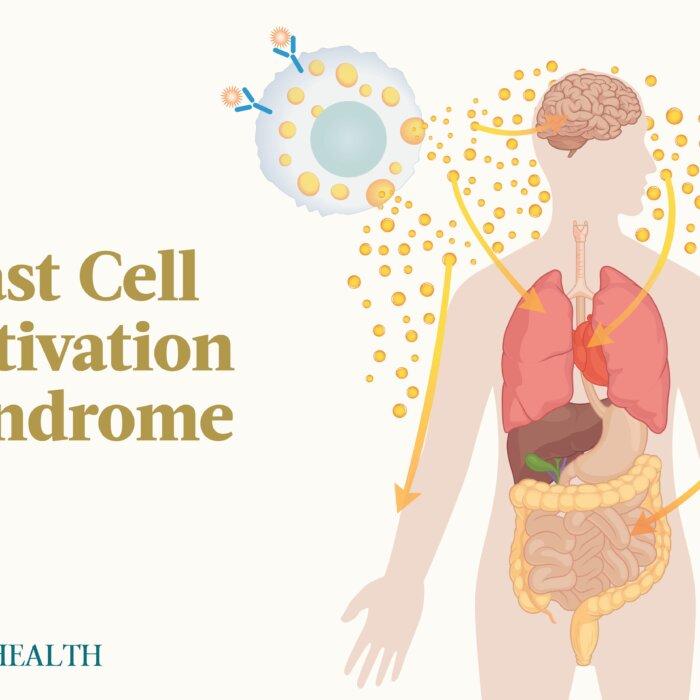

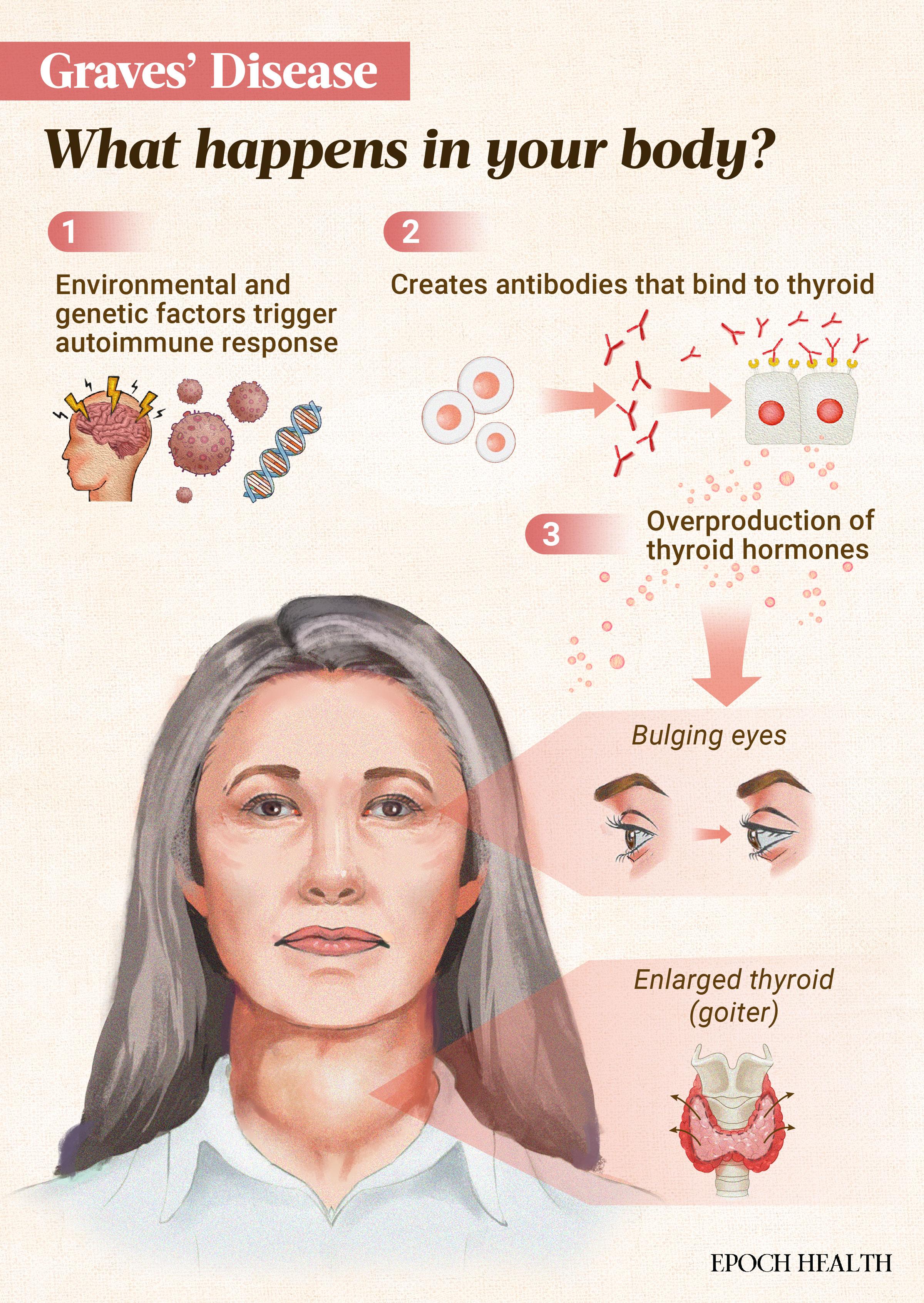

Graves’ disease is the leading cause of hyperthyroidism, or overactive thyroid, in the United States. It affects an estimated one in 100 Americans. In this autoimmune disorder, the immune system targets receptors on the thyroid gland. As a result, the thyroid produces excess thyroid hormones, triggering a potentially debilitating cascade of symptoms.

What Are the Symptoms and Early Signs of Graves’ Disease?

- Bulging eyes with decreased blinking

- Thin hair or skin

- Tremors, particularly in the hand

- Muscle weakness (myopathy)

- Visible neck swelling due to an enlarged thyroid (goiter)

- Difficulty swallowing or voice changes

- Rapid, fluttering, or irregular heartbeat

- Shortness of breath (dyspnea)

- Restlessness or insomnia

- Accelerated reflex responses

- Rapid and intense mood changes

- Nervousness, anxiety, or irritability

- Accelerated bone maturation with decreased density and increased fracture risk

- Decreased cholesterol levels

- Frequent bowel movements or diarrhea

- Increased sensitivity to heat and excessive sweating

- Unintentional weight loss despite increased appetite

- Irregular menstrual cycles for women

- Decreased libido in men

What Causes Graves’ Disease?

This enlarged thyroid is called a goiter. It can cause visible swelling and pressure in the neck. The excess thyroid hormones speed up the body’s metabolism, causing symptoms like weight loss, increased appetite, nutritional deficiencies, and heat intolerance. Additionally, this hypermetabolic state and the TSH-R-Abs can increase oxidative stress, leading to cellular damage and inflammation.

Environmental Factors

Various environmental factors have been linked to Graves’ disease, including:- Chronic stress

- Negative life experiences

- Radiation exposure

- Heavy metals

- Environmental toxins like some pesticides, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and Agent Orange

- Viruses such as Epstein-Barr, SARS-CoV-2, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and hepatitis C

- Bacterial infections, including Yersinia enterocolitica and Helicobacter pylori

- Medications, such as antibiotics, amiodarone used for heart rhythm disorders, and antivirals used to treat HIV, hepatitis C, and some cancers

- Iodine-containing contrast agents used for imaging

- Hormonal factors (particularly estrogen and progesterone)

- High-fat, high-sugar diet

Gut Health

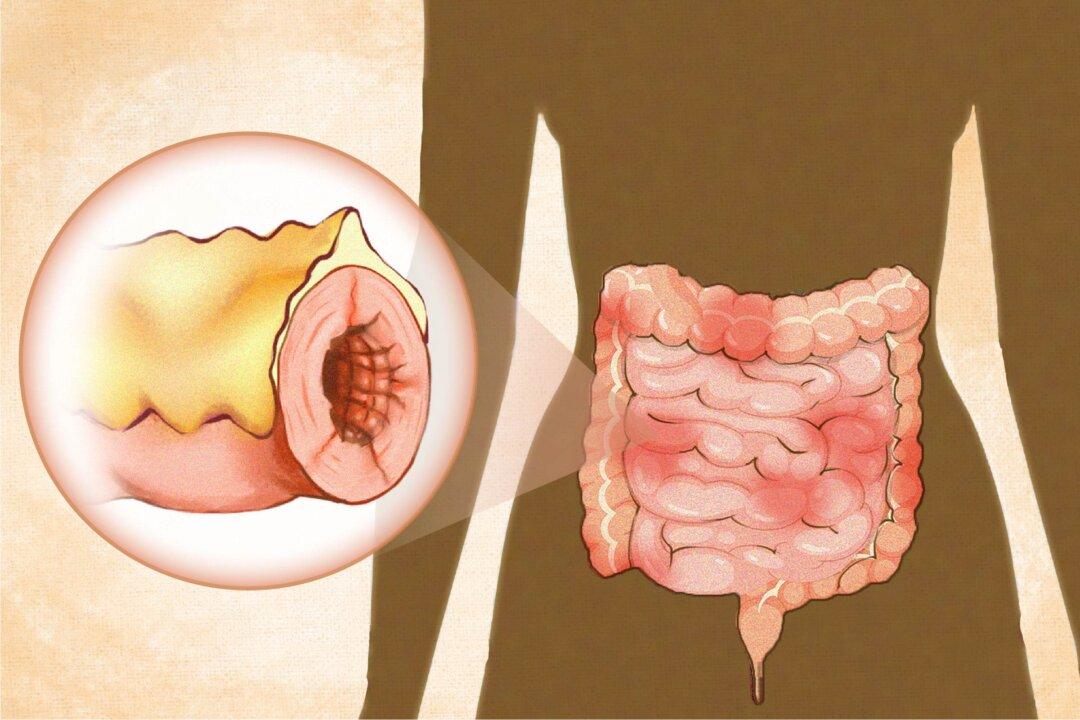

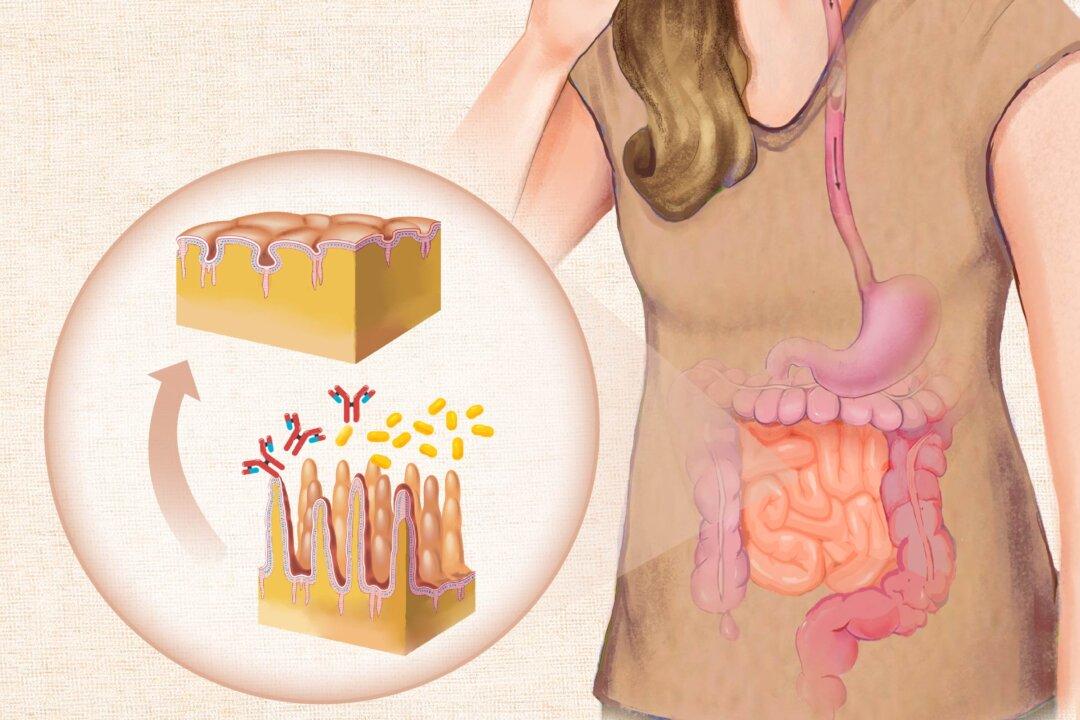

Research has highlighted the important role of gut health in the development of Graves’ disease. The gut is home to trillions of microbes, collectively called the gut microbiome. These microbes play a major role in immune system regulation. Evidence supporting the microbiome’s role includes findings that antithyroid drugs can change the microbiota composition.Disruptions in the gut microbiota (dysbiosis) and increased intestinal permeability (“leaky gut”) are associated with autoimmune thyroid conditions. In a healthy gut, the intestinal lining acts as a barrier, carefully controlling what enters the bloodstream. However, when this barrier is compromised or “leaky,” particles, toxins, and bacteria can pass through into the bloodstream. This can trigger an immune response and inflammation when the body perceives these substances as foreign invaders.

Various factors, such as those listed above, can contribute to poor gut health and dysbiosis. These can disrupt the delicate balance of gut bacteria and compromise the intestinal barrier.

Nutritional Factors

Nutritional deficiencies may contribute to the development or worsening of Graves’ disease. The increased metabolism associated with the condition raises the body’s demand for various nutrients, which can lead to deficiencies. Additionally, hyperthyroidism can cause the body to break down both muscle and fat. Potential deficiencies include:- Vitamins: A, B1, B6, B12, C, and D

- Minerals: Magnesium, selenium, and zinc

- Other essential nutrients: Protein, essential fatty acids, choline, and Coenzyme Q10.

- Iodine: While iodine is essential for thyroid function, excess can trigger or exacerbate autoimmune thyroid conditions in susceptible individuals.

- Salt: Research has shown a potential link between high salt intake and autoimmune diseases. High salt levels can stimulate the production and activation of Th17 immune cells, which are associated with inflammation and autoimmune processes.

- Gluten: Found in wheat, barley, rye, and contaminated oats, gluten is the autoimmune trigger in celiac disease, which often co-occurs with Graves’ disease. Studies also suggest a link between Graves’ disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity. Eliminating gluten may benefit some individuals with Graves’ disease by reducing inflammation and intestinal permeability.

Vaccine-Induced Graves’ Disease

Numerous case reports and case series have linked vaccines to the onset or relapse of Graves’ disease. In a recent review of 62 cases of COVID-19 vaccine-induced Graves’ disease, 76 percent were new-onset cases, and 24 percent were relapsed cases. In reports regarding the COVID-19 vaccines, the new-onset Graves’ disease cases often occurred within days, and the vast majority emerged within four weeks of vaccination. These instances were seen with the first and subsequent doses of the vaccine and with various types of it.Research regarding the link between vaccines and autoimmunity is ongoing, and causation has not been established due to limited data and a lack of large-scale clinical studies. Underreporting of cases is also a significant issue. Some practitioners may not be aware of the potential link or may not know how to report such cases. Additionally, published case reports only document a small fraction of cases.

- Molecular mimicry/cross-reactivity: This occurs when components of the vaccine resemble human proteins, causing the immune system to attack both.

- Immune system upregulation: Vaccines can overstimulate the immune system to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines, which may contribute to autoimmune responses.

- Autoantibody generation: Vaccines may trigger the production of autoantibodies in susceptible individuals.

- ASIA syndrome: Vaccines often include adjuvants, substances that enhance the body’s immune response. Examples of adjuvants include aluminum salts, polyethylene glycol, and polysorbate 80. Some vaccines, like mRNA vaccines, use lipid nanoparticles as a delivery system, which may have some immunostimulatory properties. A proposed and controversial condition called autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants (ASIA) suggests that these components may trigger autoimmunity in some individuals.

What Are the Types of Graves’ Disease?

- Thyrotoxicosis: This is the most common manifestation of Graves’ disease and refers to an excess of thyroid hormones in the body, presenting with symptoms such as rapid heartbeat, weight loss, and anxiety.

- Graves’ orbitopathy or ophthalmopathy (GO): In some patients, Graves’ disease affects the eyes, causing symptoms like bulging eyes (exophthalmos), dryness, irritation, and, in severe cases, vision problems. This condition can also include the “thyroid stare,” where the eyes appear more prominent.

- Graves’ dermopathy: This is a less common manifestation in which the skin, usually on the shins and feet, becomes thick, red, and rough. It is also known as pretibial myxedema.

- Thyroid acropachy: In this rare form, swelling and clubbing of the fingers and toes occur.

Who Is at Risk of Graves’ Disease?

- Sex: Females are up to 10 times more likely than males to develop the disease.

- Age: While Graves’ disease can occur at any age, it is more frequent between 30 and 60 years of age.

- Ethnicity: African Americans have an increased incidence.

- Family history: Having relatives with Graves’ disease increases the risk. It is estimated that genetic factors account for 60 percent to 80 percent, with environmental factors contributing the remainder.

- Autoimmunity: Having one autoimmune disorder increases the risk of developing others. One study found that about 17 percent of those with Graves’ disease have at least one associated autoimmune condition, such as vitiligo, rheumatoid arthritis, celiac disease, or Type 1 diabetes.

- Smoking: Using products containing nicotine, such as cigarettes, increases the risk of developing Graves’ disease and its recurrence. Smokers with Graves’ disease are also more likely to develop GO compared to nonsmokers with the condition.

How Is Graves’ Disease Diagnosed?

First, the health care practitioner takes a detailed medical and family history and performs a physical examination that looks for signs such as an enlarged thyroid gland, nodules, rapid heartbeat, and characteristic eye changes.

Next, blood tests are ordered to confirm hyperthyroidism to distinguish Graves’ disease.

Initial screening involves checking TSH levels. A low TSH can indicate hyperthyroidism. Further tests measure free T4 and free T3 levels. Elevated levels of these thyroid hormones help confirm hyperthyroidism.

Finally, TSH-R-Abs are measured. Elevated antibody levels confirm the diagnosis of Graves’ disease and distinguish it from other causes of hyperthyroidism.

Comprehensive Functional Medicine Assessment

While conventional practitioners focus on confirming Graves’ disease, functional medicine practitioners take a broader approach. They conduct a thorough assessment to find root causes and factors contributing to the autoimmune process. This involves exploring gut health as well as environmental and nutritional factors.- Comprehensive stool analysis

- Hormone panel

- Chronic infection screening

- Micronutrient testing

- Vitamin D testing

- Celiac disease screening

- Food sensitivity testing

- Organic acid testing

- Environmental toxin testing

- Heavy metal testing

What Are Possible Complications of Graves’ Disease?

- Thyroid storm: This is a severe, life-threatening form of thyrotoxicosis characterized by extremely high thyroid hormone levels. It can cause high fever, rapid heart rate, dehydration, and even organ failure, and requires immediate medical attention.

- Cardiovascular issues: Graves’ disease can lead to serious heart problems, including atrial fibrillation, high blood pressure, and, in severe cases, heart failure.

- Bone problems: Long-term untreated hyperthyroidism can lead to osteoporosis, increasing the risk of fractures.

- Eye problems (Graves’ orbitopathy): GO affects about 40 percent of people with Graves’ disease. In severe complications, it can double vision and vision loss.

- Thyrotoxic myopathy: Excessive thyroid hormone levels can cause thyrotoxic myopathy, a condition characterized by significant muscle weakness and wasting. This condition involves abnormal cellular metabolism of potassium and can generally be resolved with supplemental potassium.

- Pregnancy complications: Graves’ disease during pregnancy presents risks for both mother and baby. Women may experience an increased risk of pregnancy loss, premature birth, preeclampsia (high blood pressure), and thyroid storm. The baby may experience low birth weight, restricted growth, and potential developmental issues. Ideally, women should receive treatment and have their thyroid function normalized before becoming pregnant.

- Goiter complications: While a goiter is a common symptom, severe enlargement can cause difficulty swallowing or breathing.

- Mental health issues: Graves’ disease often comes with mental health disorders, such as anxiety, depression, and cognitive impairment. These issues may continue even after thyroid levels are treated and normalized.

- Long-term thyroid function changes: Interestingly, Graves’ disease and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (hypothyroid) can occur together, though this is rare. More commonly, 15 percent to 20 percent of cases shift from Graves’ disease to Hashimoto’s thyroiditis at some point after treatment.

- Pancytopenia: Graves’ disease has been linked to pernicious anemia, an autoimmune vitamin B12 deficiency. In rare cases, this can lead to pancytopenia, a reduction in red and white blood cells and platelets, causing severe anemia and other complications. Additionally, antithyroid drugs used to treat Graves’ disease can also cause pancytopenia as a rare side effect. Treatment with vitamin B12 can resolve pancytopenia caused by pernicious anemia.

What Are the Treatments for Graves’ Disease?

1. Beta-Adrenergic Blockers

Beta blockers are used in moderate to severe cases or a thyroid storm to quickly reduce blood pressure and relieve some of the symptoms of hyperthyroidism like shaking, rapid heartbeat, and anxiety. These can be stopped once thyroid hormone levels are normalized.2. Antithyroid Thionamide Drugs

Globally, antithyroid thionamide drugs (ATDs) are the preferred initial treatment for Graves’ disease for 12 to 18 months. These drugs prevent thyroid hormone production. Methimazole (MMI or MMZ) is generally the preferred ATD. Propylthiouracil (PTU), another ATD, is preferred over MMI during the first trimester of pregnancy. However, PTU is not recommended for children and adolescents due to potential liver toxicity.- They do not adversely affect GO.

- Low-dose MMI may be used long-term and is encouraged in cases likely to achieve remission.

- They have a lower risk of causing hypothyroidism compared to other treatments.

- Agranulocytosis (dangerously low white blood cell count, increasing susceptibility to infections)

- Liver toxicity

- Vasculitis (inflammation of the blood vessels, which can damage organs and tissues)

- Pancreatitis

- Hair loss

- Aplastic anemia (failure of the bone marrow to produce sufficient red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets)

- Thrombocytopenia (low platelet count, leading to increased risk of bleeding and bruising)

3. Radioactive Iodine

Radioactive iodine (RAI) may be used under the following circumstances:- Hyperthyroidism is not resolved after taking ATDs for 12 to 18 months.

- Thyrotoxicosis recurs.

- The patient exhibits poor compliance in taking ATDs.

- ATDs cause side effects.

Post-treatment, patients emit small amounts of radiation, necessitating precautions to minimize exposure to others, especially children.

- Active GO

- Increased risk of GO, such as in smokers

- Nodular goiter with suspected thyroid cancer

- Pregnancy

- Breastfeeding

- Severe thyrotoxicosis or thyroid storm

- Sialadenitis (inflammation of the salivary glands)

- Painful radiation thyroiditis

- Increased risk of certain cancers

- Negative impacts on female fertility and earlier menopause

4. Thyroidectomy

Surgery to remove some or all of the thyroid is a permanent way to stop thyroid hormone production. It quickly controls the overactive thyroid without radiation, usually without worsening GO. However, it results in permanent hypothyroidism, which requires taking thyroid hormones for life.- Laryngeal nerve injury, with consequential voice changes or hoarseness

- Hypoparathyroidism (low calcium levels due to damaged parathyroid glands)

- Hypocalcemia (temporary or permanent low blood calcium causing muscle cramps or tingling)

How Does Mindset Affect Graves’ Disease?

- Reduced production of TSH

- Release of stress hormones (glucocorticoids and catecholamines)

- Increased production of inflammatory cytokines

Interestingly, research has also demonstrated the power of how we view our own health. A person’s self-assessment of their health can predict how likely they are to get sick or how long they might live. Surprisingly, these self-assessments often turn out to be more accurate than a doctor’s evaluation. This underscores the importance of maintaining a positive yet realistic view of one’s health status.

What Are the Natural Approaches to Graves’ Disease?

Natural Supplements and Botanicals

Graves’ disease can be a serious condition that requires careful management. Therefore, it is essential to work with an integrative or functional medicine practitioner skilled in supplementation. He or she can determine which supplements, forms, and dosages are appropriate for your individual case. The following are some natural supplements that have been shown to reduce hyperthyroidism or its symptoms in Graves’ disease:- L-carnitine: Research shows that L-carnitine can reduce and prevent symptoms of hyperthyroidism and increase bone mineral density. It works by inhibiting the entry of T3 and T4 into the cell nuclei and is useful in thyroid storm or when a lower dose of MMI is required. High doses may cause stomach upset or diarrhea. These results are not applicable to acetyl-L-carnitine, D-carnitine, or DL-carnitine.

- Selenium: Selenium supplementation may help achieve remission and enhance the effectiveness of ATDs. When combined with L-carnitine, one pilot study found that selenium reduced symptoms of hyperthyroidism and improved quality of life.

- Lemon balm (Melissa officinalis): Lemon balm extract can help manage hyperthyroidism by reducing thyroid hormone levels. In animal studies, it decreased oxidative stress and improved thyroid gland structure.

- Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10): This potent anti-inflammatory agent and antioxidant is often low in people with hyperthyroidism. Preclinical research and small studies suggest proper supplementation can restore optimal levels and improve cardiac function within one week in those with hyperthyroidism.

The 5R’s Functional Medicine Approach

The 5R approach in functional medicine can be particularly beneficial in managing Graves’ disease. Even after RAI or thyroidectomy, most of these therapies can still benefit Graves’ disease and overall health. The steps involved in this approach include the following:- Remove: Treat infections, minimize exposure to toxins, and eliminate foods that cause inflammation, such as gluten, dairy, soy, ultra-processed foods, and sugars. Avoid factors that increase intestinal permeability, including alcohol, certain medications, and stressors. Avoid caffeine if it increases heart rate or anxiety.

- Replace: Supplement digestive enzymes and essential nutrients that may be deficient. A broad-spectrum, high-potency multivitamin and mineral supplement can provide general nutritional support and antioxidants to combat oxidative stress. Balance hormones as indicated by testing. Because supplement quality can vary drastically, it’s important to ensure professional-grade quality or enlist a health care practitioner to help.

- Reinoculate: Rebuild the gut microbiome with prebiotic and probiotic foods and supplementation based on stool analysis.

- Repair: Use gut-healing nutrients like collagen peptides, glutamine, curcumin, zinc L-carnosine, vitamins A and D, and omega-3 fatty acids to protect and repair the gut lining and help reduce inflammation.

- Rebalance: Make lifestyle modifications to reduce stress, prioritize sleep, increase movement, and improve work–life balance. Eat an anti-inflammatory, nutrient-dense diet rich in whole foods.

Due to the loss of muscle and fat associated with Graves’ disease, eating sufficient amounts of healthy proteins and fats every day is critical.

The National Academy of Medicine recommends a daily intake of 0.8 gram of protein per kilogram of body weight for adults. However, individual needs may vary based on activity level and overall health. For example, athletes or very active individuals may need more. Good sources include eggs, legumes, and wild or lean, naturally raised meats, poultry, and fish. Vary protein sources in your diet.

How Can I Prevent Graves’ Disease?

- Buy organic: Pesticides, herbicides, and some fertilizers used on conventionally grown crops have thyroid-disrupting properties. Widely used glyphosate, in particular, has been shown to disrupt the HPT axis by decreasing TSH concentrations and altering gene expression related to thyroid hormone transport and metabolism. It also alters gut microbiota.

- Avoid plastic containers: Bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates, and polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) contaminate food through plastic containers and have thyroid-disrupting effects.

- Avoid other toxic chemicals: Brominated flame retardants and perfluorinated chemicals found in furniture, water-resistant clothing, and nonstick cookware have thyroid-disrupting effects.

- Invest in a good water filtration system: Water can be contaminated with perchlorate, nitrates, fluoride, and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), which can disrupt thyroid function. Chlorinated water can also disrupt the gut microbiota.

- Consume omega-3 fatty acids: Consume foods rich in omega-3 fatty acids, or consider fish oil supplements. These have anti-inflammatory effects and may help prevent Graves’ disease in those exposed to endocrine disruptors.

- Maintain a healthy gut: A balanced gut microbiome and functional gut barrier play crucial roles in immune function and overall health. Eat a diverse, fiber-rich diet and consider probiotic foods or supplements to support gut health.

- Avoid smoking: Also avoid exposure to secondhand smoke.

- Moderate salt intake: Sodium is a necessary mineral, but high salt intake can drive inflammation and the autoimmune process. Avoid processed foods and use sea salt or Himalayan pink salt in moderation.

- Manage stress levels: Find healthy outlets for stress, such as yoga, meditation, qigong, or breathwork.