Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease and, in Europe, Charcot’s disease is a serious neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the progressive weakening and wasting of muscles. ALS slowly takes away the ability to walk, eat, and breathe.

What Are the Symptoms and Early Signs of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis?

ALS symptoms can be categorized by their initial onset or significance in supporting a diagnosis.

- Weakness in the ankle, finger, or upper arm

- Muscle atrophy, especially around the thumb

- Muscle twitches and cramps in a weak limb

- Loss of coordination

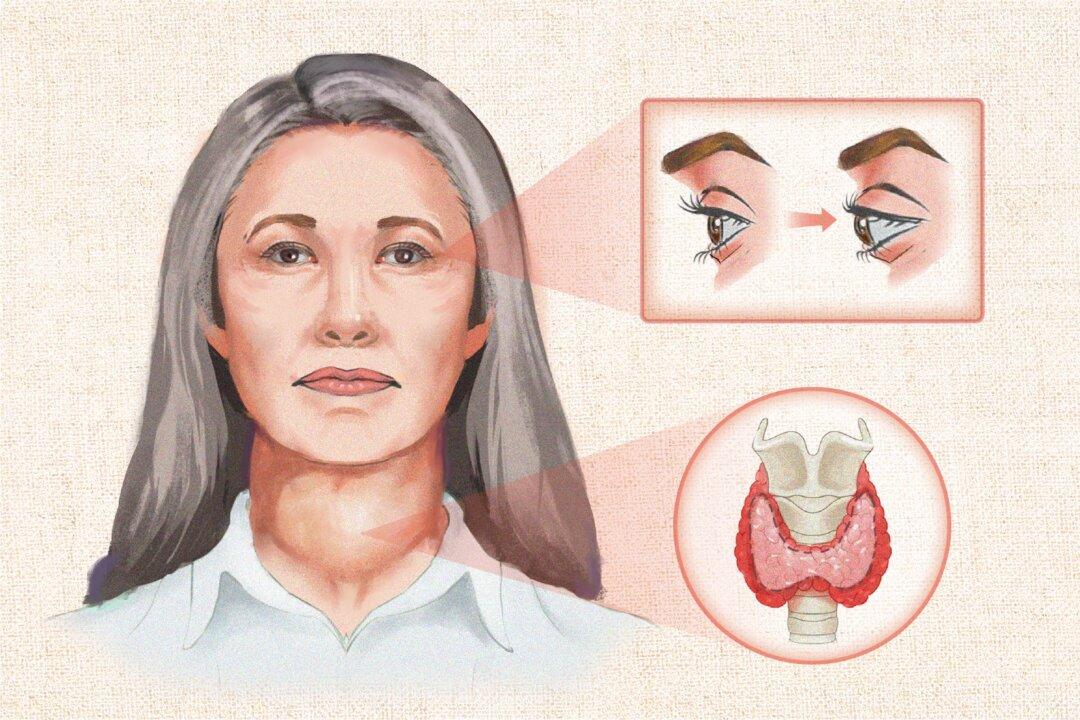

- Slow or slurred speech

- Vocal pitch changes

- Weakness in the neck muscles

- Difficulty swallowing or chewing, with possible weight loss or malnutrition

- Coughing while drinking water

- Excessive saliva or mucus, causing drooling or frequent throat-clearing

- Twitches or atrophy of the tongue

- Changes in cognitive function

- Intense and rapid mood swings

- Sudden, uncontrollable episodes of crying or laughing, disproportionate to the situation

- Progressive, unintentional weight loss

- Difficulty walking or unexplained falls

- Difficulty breathing when lying flat (orthopnea)

- Weakness in one side of the diaphragm (hemidiaphragm weakness)

- Speech that weakens or worsens at the end of the day

- Exaggerated reflexes (hyperreflexia) with muscle loss (atrophy) and weakness

What Causes Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis?

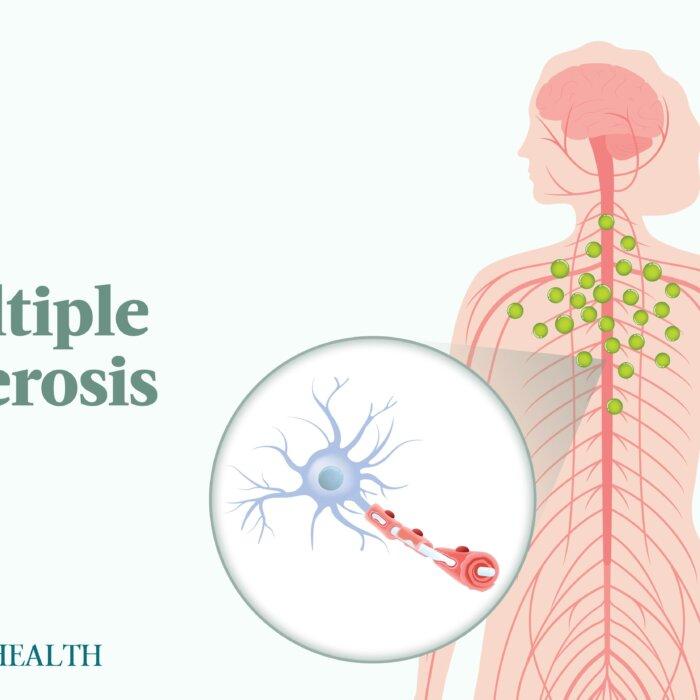

- Amyotrophic: “A” means no, “myo” means muscle, and “trophic” means nourishment, indicating no nourishment to the muscles

- Lateral: Refers to the sides of the spinal cord where nerve cells that control muscles are located

- Sclerosis: Means scarring or hardening

Researchers used to think ALS only affected the nerves that control movement, but they now know it can also cause changes in cognition and behavior. About 10 to 15 percent of those with ALS develop frontotemporal dementia, and up to half may have some degree of cognitive impairment.

Pathological Processes

The following are some of the key potentially disease-causing processes involved in ALS:- Defective axonal transport: When the movement of materials along nerve fibers (axons) is impaired, it disrupts communication between neurons and muscles.

- Glial cell dysfunction: Glial cells normally support and protect neurons, but when they malfunction, they can contribute to nerve cell damage.

- Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress: The ER is a part of the cell that helps fold and process proteins. If too many misfolded proteins build up, it triggers a stress response that can damage or kill neurons.

- Oxidative stress: An imbalance between harmful free radicals and protective antioxidants can damage cells.

- Glutamate excitotoxicity: When the neurotransmitter glutamate is overactive, it can harm neurons.

- Protein aggregation: Abnormal clumping of proteins can form inclusion bodies, which disrupt normal cell function.

- Impaired DNA and RNA metabolism: Changes in how genetic material is processed can affect neuron health.

- Mitochondrial dysfunction: Problems with energy production in cells can lead to neuronal damage.

- Apoptosis: Excessive programmed cell death contributes to the loss of motor neurons in ALS. This can be triggered by factors like oxidative stress and calcium influx into neurons.

- Neuroinflammation: Chronic inflammation in the nervous system can damage motor neurons.

Environmental Factors

Some of the environmental influences that may contribute to the development and progression of ALS are:- Toxicants: Exposure to heavy metals, persistent pollutants, and other environmental toxicants has been shown to trigger ALS.

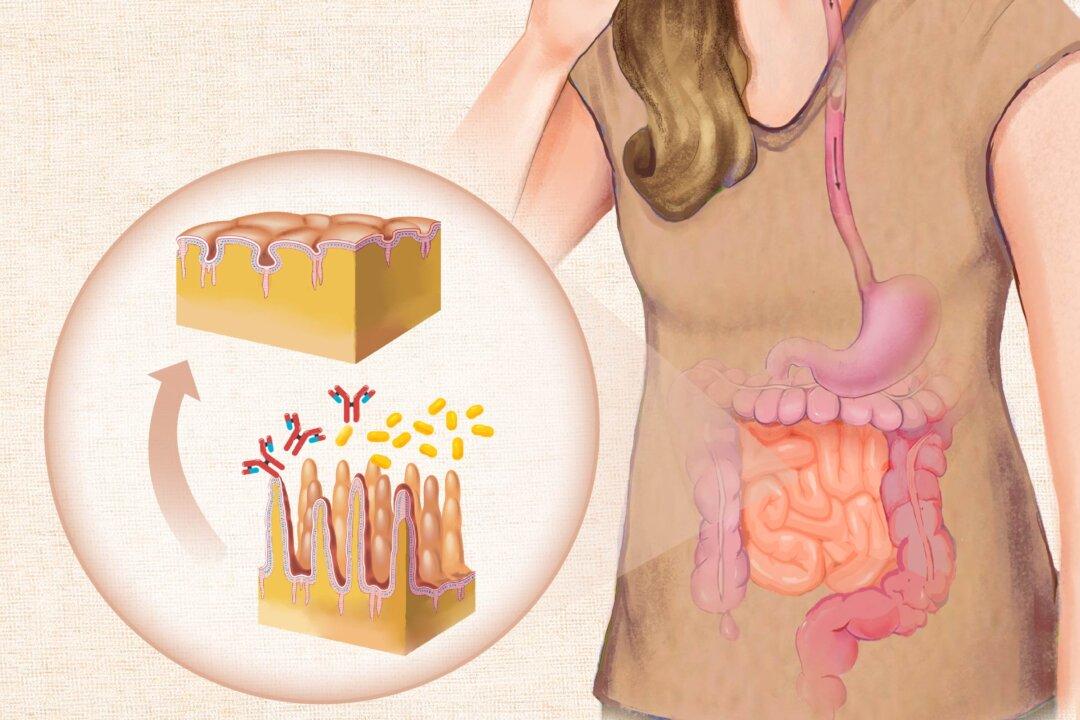

- Microbiome dysbiosis: Recent research suggests that the balance of bacteria in our gut, known as the microbiome, may play a role in ALS. Imbalances, known as dysbiosis, can contribute to inflammation and metabolic changes, potentially influencing the disease’s emergence and development.

- Sleep impairment: Chronic sleep problems may contribute to ALS progression by disrupting the glymphatic system, which clears waste and protein build-up from the brain. When this system fails to work properly, harmful substances like protein aggregates and glutamate can accumulate, leading to neuronal damage.

- Strenuous exercise: Strenuous sports and exercises involving anaerobic bursts of activity can raise the risk of ALS in those who are genetically predisposed. The risk increases with the frequency and intensity of the exercise. Genetic testing can help identify individuals at risk, allowing for personalized exercise plans. Notably, sedentary behavior does not offer protection, and for those without a genetic predisposition, moderate physical activity is generally beneficial.

- Viruses: Neuronal degeneration can be caused directly or indirectly by viruses, some of which can establish persistent infections in the central nervous system. Enteroviruses, such as poliovirus, have been observed to trigger cellular changes characteristic of ALS, suggesting that chronic infections by these viruses might contribute to ALS development.

What Are the Types of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis?

- Sporadic ALS: This is the most common form, accounting for approximately 90 percent of cases, and occurs without a known family history.

- Familial ALS: This form accounts for about 10 percent of cases and is inherited, often linked to specific genetic mutations.

- Bulbar: Characterized by speech and swallowing difficulties

- Respiratory: Primarily affects respiratory muscles

- Flail Arm: Involves weakness and atrophy in the arms

- Classical: Features both upper and lower motor neuron signs in multiple regions

- Pyramidal: Predominantly involves upper motor neuron signs

- Flail Leg: Involves weakness and atrophy in the legs

Who’s at Risk of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis?

- Age: ALS is a disease that can occur in adults at any age. Being between 55 and 65 years old is considered a risk factor for ALS, while familial ALS typically occurs at a younger age. As individuals age, cellular damage accumulates, and the ability to repair and regenerate tissues diminishes, coupled with a lifetime of exposure to environmental factors. These age-related changes increase the vulnerability of motor neurons, making aging a significant risk factor for ALS.

- Gender: Males are slightly more likely to develop ALS than females, though the difference decreases with age.

- Ethnicity: In the United States, ALS incidence is lower among African, Asian, and Hispanic ethnicities compared to whites.

- Location: ALS incidence is slightly higher in Europe and North America compared to other regions. Asian populations tend to have lower incidence rates, while New Zealand, part of Oceania, reports some of the highest incidence rates.

- Family history: Having a family member with ALS, increases the likelihood of developing the disease.

- Military service: Research indicates a higher risk of ALS among military personnel, likely due to exposure to intense physical exertion, trauma, and environmental contaminants. This increased risk is especially noted in veterans of World War II and the Gulf War, although the exact reasons remain unclear.

- Smoking: Findings of a recent systematic review and meta-analysis confirmed that cigarette smokers, especially women, have a higher risk of developing ALS than non-smokers. The risk increases with both the length of time spent smoking and the amount smoked.

- Certain viruses: While some viruses are believed to contribute to the development of ALS, others are associated with an elevated risk of developing it. These viruses include influenza and pneumonia.

- Occupational factors: Exposure to diesel exhaust, agricultural chemicals (herbicides, fungicides, and insecticides), solvents, metals (such as mercury and lead), formaldehyde, and silica dust can increase the risk. Note mercury exposure can also occur through amalgam dental fillings and contaminated fish and seafood.

- Hobbies: Lead exposure, which is linked to increased risk, can also occur from activities such as casting or reloading bullets, making stained glass, or using fishing sinkers.

- Residential factors: Air pollution, use of lawn and garden chemicals, drinking water containing private well water, exposure to manganese in drinking water or soil, and living near agricultural crops have been suggested as potential risk factors.

- Trauma: Head trauma, particularly severe or repeated injuries, and injuries 10 or more years prior to diagnosis, has been associated with an increased risk of ALS. Electric shock and exposure to extremely low-frequency electromagnetic fields have also been suggested as potential risk factors. The risk associated with these traumas may be even higher for decades-old injuries over recent ones.

Factors Impacting Outcomes and Survival

Beyond the factors increasing the risk of developing ALS, certain factors have been found to influence prognosis. Predicting the prognosis for any individual with ALS is impossible, with disease progression and outcomes varying greatly. While the median survival time is about 30 months after diagnosis, a significant minority of people live longer. In fact, 10 to 20 percent of individuals survive beyond five years, and 5 to 10 percent live beyond ten years. Factors influencing prognosis include:- Age at onset: Older age at the onset of ALS symptoms is consistently associated with a worse prognosis. Younger patients tend to have a longer survival time.

- Site of onset: Bulbar onset is generally associated with a poorer prognosis compared to limb onset. Individuals with bulbar onset are likely to progress more rapidly and develop cognitive impairment.

- Rate of disease progression: A faster rate of symptom progression is an independent prognostic factor for worse outcomes.

- Respiratory function: Poor respiratory function at diagnosis is linked to a shorter survival time. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) has been found to improve survival.

- Nutritional status: Malnutrition and weight loss are associated with a worse prognosis.

- Psychosocial factors: Factors such as the presence of frontotemporal dementia, stress, depression, and feelings of hopelessness can shorten lifespan.

- Access to supportive care: Access to comprehensive care and support can improve quality of life and potentially extend survival.

- Marital status: Being married has been shown to lead to better outcomes than living alone.

How Is Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Diagnosed?

Before referring a patient to a neurologist, a primary care practitioner might suspect ALS based on the patient’s symptoms, signs, and family history. The practitioner will perform a thorough physical and neurological exam and check cognitive function.

- Electrodiagnostic tests: Electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies (NCS) assess muscle and nerve function. These tests can identify patterns of nerve damage characteristic of ALS and help rule out conditions like peripheral neuropathy.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): An MRI provides detailed images of the brain and spinal cord. While ALS typically does not show specific changes on an MRI, this test can exclude other possible causes of symptoms, such as tumors or herniated discs.

- Blood and Urine Tests: These tests are used to rule out other diseases that might mimic ALS symptoms, such as infections or metabolic disorders.

- Muscle or Nerve Biopsy: In some cases, a biopsy may be performed to differentiate ALS from other muscle diseases.

- Spinal Tap (Lumbar Puncture): This procedure involves collecting cerebrospinal fluid to rule out other conditions like infections or inflammatory diseases that could cause similar symptoms.

- Genetic Testing: If there is a family history of ALS, genetic testing may be conducted to identify mutations associated with familial ALS.

Monitoring Disease Progression

To monitor disease progression, health care providers use the ALS Functional Rating Scale (ALSFRS) and its revised version, ALSFRS-R. The ALSFRS-R is more comprehensive, including assessments for respiratory functions. It consists of 12 items, with higher scores indicating better physical function. This scale is widely used in clinical trials and is considered the gold standard for tracking ALS progression.Functional Medicine Tests

A functional medicine practitioner may order additional tests to assess underlying pathological processes and environmental factors that could be contributing to ALS symptoms or progression. These tests can help guide personalized treatment strategies and might include:- Oxidative stress markers: Tests that measure levels of antioxidants and free radicals in the body, which can indicate cellular damage.

- Heavy metal analysis: Assesses exposure to toxic metals like lead, mercury, or aluminum, which may contribute to neurological issues.

- Chemical toxicity screening: Identifies the presence of environmental toxins or pesticides that could be impacting neurological health.

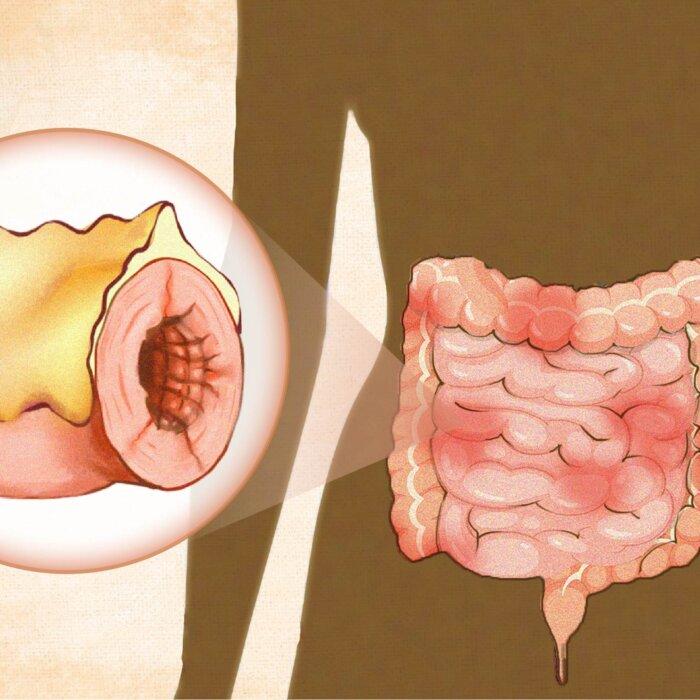

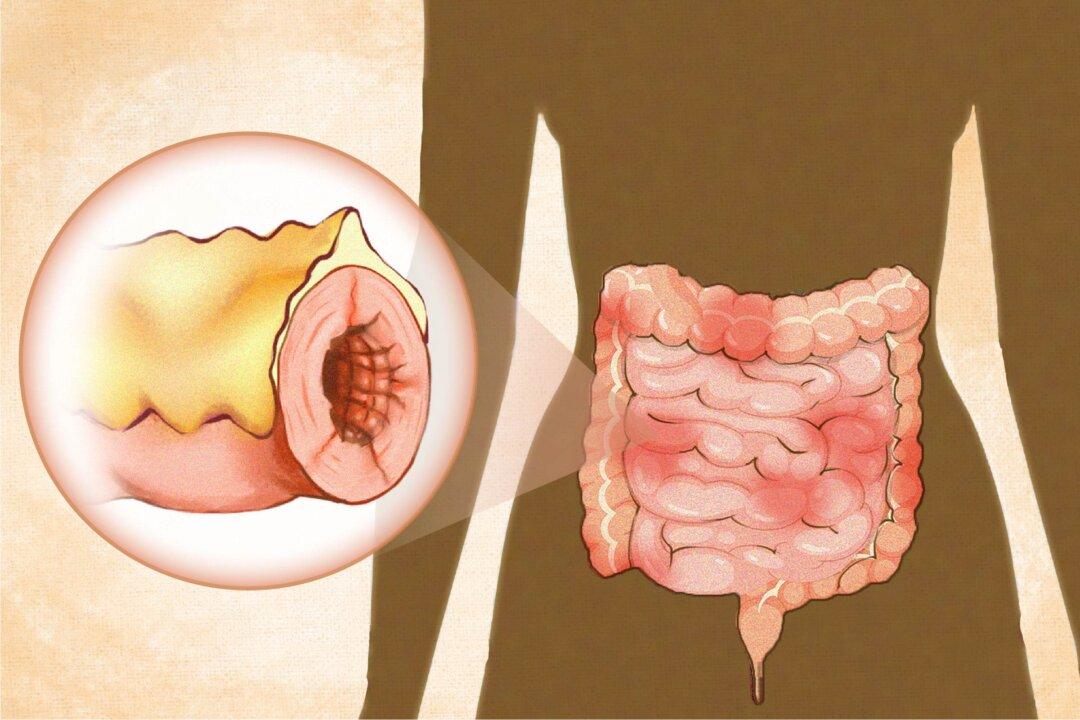

- Comprehensive stool analysis: Evaluates gut health, including microbiome composition, digestive function, and inflammation markers.

- Nutrient deficiency tests: Checks for levels of essential vitamins and minerals that support neurological health.

- Inflammatory markers: Measures indicators of systemic inflammation, which may contribute to ALS progression.

What Are Possible Complications of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis?

- Cognitive impairment, including trouble with short-term memory, controlling impulses, and speaking smoothly

- Frontotemporal dementia

- Behavioral changes, including apathy, irritability, and poor hygiene

- Insomnia, sleep difficulties

- Depression and anxiety

- Respiratory complications

- Muscle cramps and stiffness

- Communication difficulties

- Aspiration pneumonia (a lung infection caused by inhaling food, liquid, or saliva)

- Nutritional deficiencies from a lack of sun exposure and swallowing difficulties, which can lead to insufficient food intake

- Pressure sores (bed sores) from prolonged periods of sitting or lying down

What Are the Treatments for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis?

These interventions can stabilize weight, improve respiratory function, and ultimately extend life expectancy while enhancing the quality of life for those living with ALS. These medical advances have changed the expected trajectory of the disease, making it less predictable and more variable based on the care received.

Current treatments include:

1. Medications:- Riluzole (Rilutek): This oral medication is believed to reduce damage to motor neurons by decreasing levels of glutamate, a neurotransmitter that, in excess, can be toxic to nerve cells. It may prolong survival by a few months and is available in various formulations for those with swallowing difficulties.

- Edaravone (Radicava): An antioxidant administered orally or intravenously, edaravone has been shown to slow the decline in daily functioning in some patients with ALS, particularly in those with early-stage disease or a rapid progression rate. It works by reducing oxidative stress, which is believed to contribute to motor neuron damage in ALS.

- Tofersen (Qalsody): In individuals with superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) gene mutations, which represent 20 percent of all ALS cases, SOD1, typically an antioxidant, can become neurotoxic. Approved in 2023 specifically for patients with these mutations, Tofersen is administered via spinal injection and has been shown to reduce levels of a nerve damage marker (NfL), potentially slowing disease progression and extending survival. Its long-term benefits are still under study.

- Nutritional Support: Enteral nutrition may be provided to help maintain weight and ensure proper nutrition for those who have difficulty eating. This involves delivering nutrients directly into the gastrointestinal tract through a tube called a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube. Placing the PEG tube within 12 to 24 months after diagnosis has been found to provide a survival advantage.

Non-Invasive Positive Pressure Ventilation (NIPPV) involves using a mask or nasal device to help with breathing. This type of respiratory support can improve both quality of life and survival by helping individuals breathe when muscles become too weak.

Physical, occupational, and speech therapy focus on maintaining function and communication.

- Gene therapy: This approach involves using viral vectors to deliver therapeutic genes to target cells, aiming to slow or halt disease progression by addressing specific genetic mutations associated with ALS.

- Cellular therapy: This strategy focuses on using stem cells, including induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), to repair or replace damaged neurons, offering a possible way for regenerating neural tissue and supporting neuronal function.

- Medical ozone therapy: Traditionally used in alternative medicine, studies are exploring its use in conventional medicine for potential neuroprotective and metabolic benefits in ALS. It can be harmful at the wrong dose, with potentially serious side effects, so it should be administered by an experienced, qualified practitioner.

Ongoing and Increasing Care Needs

As ALS progresses, the level of care required often increases significantly. Many individuals will eventually need full-time or in-home care to manage daily activities and ensure safety and well-being. This care may include help with transferring, bathing, dressing, and eating. Planning for these needs early can ease the transition and ensure the necessary support is in place.In-home care options range from the help of family members to hiring professional caregivers or using home health care agencies. These services help manage the physical needs of the patient and offer respite for family caregivers, supporting their well-being.

To further support safety and mobility, fall prevention measures should be implemented in the home. This may include removing tripping hazards, installing grab bars, and ensuring adequate lighting. As mobility decreases, other walking aids or a powered wheelchair may become necessary to maintain independence and prevent falls. Additionally, a hospital bed can provide comfort and facilitate care by allowing for easier positioning and transfers.

How Does Mindset Affect Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis?

His positive mental outlook and relentless pursuit of his scientific work exemplify how a strong mindset can impact one’s quality of life and longevity. Hawking often spoke about how facing the possibility of an early death made him appreciate life more deeply and motivated him to accomplish his goals. He believed that maintaining a sense of purpose and engaging in meaningful activities contributed to his resilience.

What Are Natural Approaches to Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis?

While these therapies are popular and have a long history of use, the level of evidence supporting their effectiveness varies. Working with a qualified practitioner can help ensure the right doses and forms of alternative therapies.

Nutrient-Dense Diet

Adequate caloric intake is vital in ALS due to increased energy needs. A diet rich in nutrient-dense foods, including avocados, nuts, seeds, and olive oil, provides essential fatty acids and antioxidants that support nerve health and reduce oxidative stress. Research suggests that higher intake of antioxidants, carotenes, fruits, and vegetables is associated with better ALS function at diagnosis.Natural Enteral Nutrition Alternatives

Organic, whole-food formulas offer a natural alternative to synthetic enteral nutrition. These plant-based options provide complete nutrition without artificial additives.B Vitamins

B vitamin deficiencies can lead to neurological impairments and elevated homocysteine levels, which are harmful in ALS. These elevated levels can be corrected with adequate intake of folate and vitamin B12. Administered intramuscularly, twice a week, high-dose methylcobalamin, a natural form of B12, has shown promise in treating early-stage ALS. It slowed disease progression by 43 percent. A long-term Japanese study found that methylcobalamin extended the time to major events, such as the need for full ventilation or death, by over 600 days.Mineral Balance

Maintaining balanced levels of zinc, copper, calcium, and selenium is crucial for neurological health. Imbalances can contribute to oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, excitotoxicity, neuroinflammation, and neurodegeneration, while proper levels may be protective.Vitamin D

Low vitamin D levels are common in ALS and are associated with a higher risk of death. Supplementing with 2000 IUs for nine months resulted in a smaller decline in ALS ALSFRS scores, suggesting a slowing of disease progression.Vitamin E

Higher vitamin E levels may be protective against ALS due to its antioxidant properties.N-acetylcysteine (NAC)

NAC boosts glutathione, an antioxidant, and may protect brain health, reduce oxidative stress, and lower inflammation. While it is mainly used in ALS to help with bronchial secretions, some animal studies suggest that NAC might also help slow down disease progression and improve survival. Further research is needed to confirm this in humans.Astaxanthin

Astaxanthin, an antioxidant found in marine organisms like shrimp and salmon, may offer neuroprotective benefits in ALS by reducing oxidative stress and inflammation.Acetyl-L-carnitine (ALCAR)

ALCAR is prescribed for ALS treatment in Italy and shows promise in clinical trials. A recent meta-analysis revealed that ALCAR supplementation significantly slowed the decline of physical abilities in ALS patients. The neuroprotective effects of ALCAR may stem from its ability to enhance mitochondrial function, reduce oxidative stress, and promote nerve growth factor production. While a phase III clinical trial is pending, ALCAR is generally considered safe and is well tolerated.Acupuncture and Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM)

Acupuncture, including a traditional Korean form, Saam acupuncture, shows potential in improving ALS symptoms. In a case report, the TCM formula Dihuang Yinzi has reported benefits in muscle strength, better speech, swallowing, and quality of life.Muscle Relief

Magnesium, exercise, massage, or hydrotherapy can be used to alleviate cramps, and stretching can help eliminate stiffness.Meditation

A mindfulness-based meditation program tailored for ALS patients has been shown to improve quality of life, reducing anxiety and depression while enhancing emotional well-being and social interactions.Microbiome Balance

Differences in gut bacteria between ALS patients and healthy individuals suggest potential benefits from microbiome balancing. Akkermansia muciniphila bacteria has shown promise in reducing ALS symptoms and improving neuron function in mice. A stool analysis can help assess specific imbalances, and working with a professional who understands different probiotic strains is important for creating a personalized plan.How Can I Prevent Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis?

- Adopt an anti-inflammatory diet: Include foods rich in omega-3 fatty acids, such as salmon and flaxseeds, and antioxidants like berries and leafy greens. These nutrients support nerve health, reduce oxidative stress, promote mitochondrial function, and help control neuroinflammation.

- Engage in regular physical activity: Moderate exercise such as walking, swimming, or yoga can improve circulation, support detoxification, reduce neuroinflammation, enhance mitochondrial function, and help manage oxidative stress.

- Limit exposure to toxins: Use natural household and personal care products, and avoid exposure to herbicides, pesticides, and heavy metals to help reduce neuroinflammation, prevent excitotoxicity, and support mitochondrial health.

- Practice stress reduction techniques: Techniques such as meditation, deep breathing, and mindfulness can help reduce stress and inflammation, supporting overall brain health and reducing excitotoxicity.

- Prioritize quality sleep: Create a restful environment and practice good bedtime habits consistently to optimize sleep. Aim for seven to nine hours of restful sleep each night. Adequate sleep supports muscle repair and tissue growth, enhances mitochondrial function, and regulates oxidative stress.

- Avoid smoking: Smoking introduces heavy metals and other chemicals like formaldehyde that can increase oxidative stress, contribute to neurotoxicity, and exacerbate inflammation, all of which may increase the risk of ALS and worsen its progression.