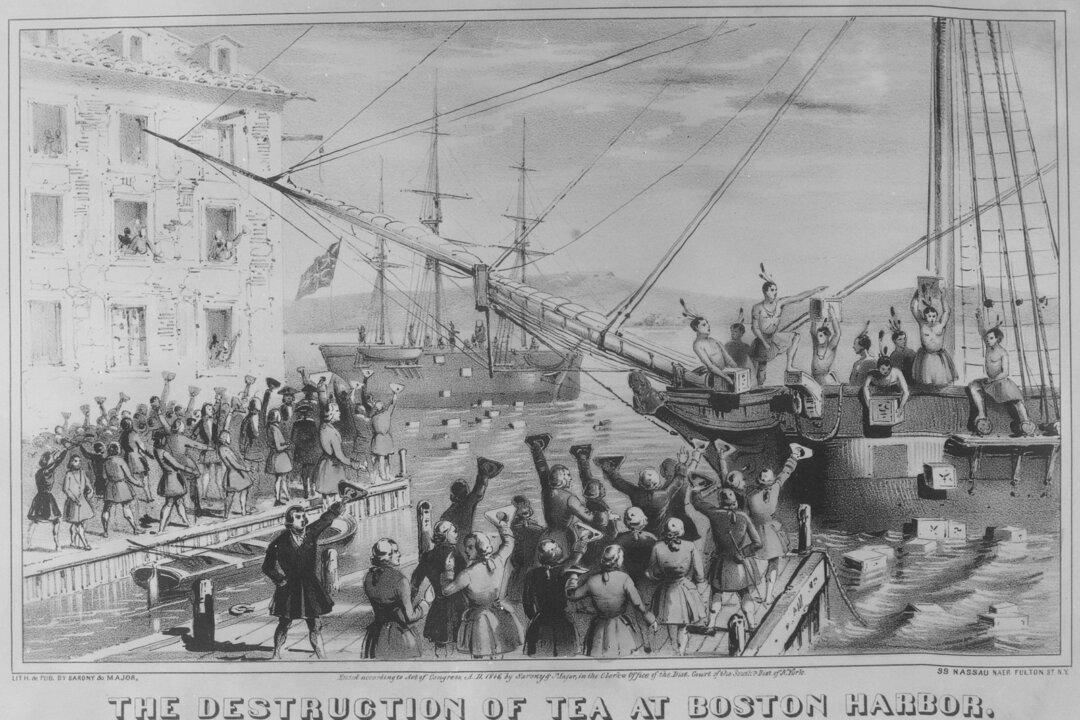

In April 1774, disturbing rumors began to spread in the American colonies about Britain’s response to the Boston Tea Party, then referred to as the Destruction of the Tea. Letters from diplomats Arthur Lee, Benjamin Franklin, and others in London warned of harsh retaliatory measures being discussed in Parliament.

On May 10, those rumors were realized when the people of Boston received the full text of the Boston Port Act (also called the Port Bill). This was the first in a series of four measures known as the Coercive Acts, which were aimed at collectively punishing Massachusetts Bay for the destroyed tea, its role in the seditious act, and its failure to identify the perpetrators.

The Port Bill ordered the closure of Boston’s port and the relocation of the colonial government to Salem. It was to remain in effect until the colony reimbursed the East India Company for its losses and its people ceased their treasonous behavior.

To ensure strict compliance with the Port Bill, the British government would post redcoat regiments in Boston as an occupying force and replace the civilian governor of Massachusetts Bay, Thomas Hutchinson, with a military governor, Lt. Gen. Thomas Gage. At the same time, Adm. John Montagu would position Royal Navy warships in and around the Port of Boston to enforce a naval blockade.

Ingfbruno

IngfbrunoReactions From the Other Colonies

Within a week, news of the Port Bill reached Philadelphia and New York City, then quickly spread to other colonies. The American reaction was largely uniform: shock at the severe penalties, outrage at the arbitrary nature of the law, and fear that they too might suffer the same fate as Massachusetts Bay.However, opinions varied on how to respond. As we see today among the 50 states, each colony then had distinct political views and a wide range of opinions.

Radicals, also known as Whigs and patriots, such as Patrick Henry, Christopher Gadsden, and the Sons of Liberty, embraced a no-compromise, confrontational stance, and were willing to escalate the situation to defend their inalienable rights and freedoms granted by the “Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God.” They believed that boycotting British imports was the most effective way to challenge Parliament’s overreach.

Conservatives, also known as Tories and loyalists, such as Joseph Galloway, and moderates such as Quakers and merchants who relied on trade, opposed boycotts, fearing they would cripple American businesses and further damage relations with Britain. Conservatives rejected the concept of Natural Law, insisting that their rights were rooted in the British Constitution.

Envisioning the 1st Continental Congress

To address the growing crisis, the intercolonial network known as the Committees of Correspondence became the central hub for business and political leaders calling for a general assembly of delegates from each colony to convene in Philadelphia—an event that became known as the First Continental Congress. However, such a summit would be unauthorized by the Crown and viewed by royal authorities as bordering on treason, especially because all colonial governors—except Gov. Jonathan Trumbull of Connecticut—expected their constituents to obey all laws and acts passed by Parliament and sanctioned by King George III.Members of colonial legislatures who opposed these unsanctioned assemblies did all they could to obstruct the process. As a result, several colonies turned to extralegal revolutionary bodies, such as the Committees of Correspondence, to plan and organize the event.

In South Carolina, an illegal “general meeting of the inhabitants” was held to elect its delegates and form a committee that functioned as a provisional government.

Virginia’s colonial legislative body, the House of Burgesses, scheduled a day of fasting, humiliation, and prayer for June 1, 1774. Virginia’s governor, Lord Dunmore, found this proclamation unacceptable and immediately dissolved the colonial legislature. Summoning the House members to his Council Chamber, he declared, “Mr. Speaker and Gentlemen of the House of Burgesses, I have in my hand a paper published by order of your House, conceived in such terms as reflect highly upon His Majesty, and the Parliament of Great Britain, which makes it necessary for me to dissolve you; and you are dissolved accordingly.”

The following day, the deposed members of the now-defunct House of Burgesses met at the Raleigh Tavern to discuss the Continental Congress. There, they condemned Parliament and the East India Company for mistreating the colonists and called for a boycott of all East India Company goods “until the grievances of America are redressed.”

“We are farther clearly of opinion, that an attack made on one of our sister colonies, to compel submission to arbitrary taxes, is an attack made on all British America, and threatens ruin to the rights of all. ... for this purpose it is recommended to the committee of correspondence, that they communicate with their several corresponding committees on the expediency of appointing deputies from the several colonies of British America, to meet in general congress, at such place annually as shall be thought most convenient,” they stated.

Upstateherd

UpstateherdIn Pennsylvania’s colonial legislative body, the Provincial Assembly, Galloway and other conservative politicians, along with Gov. John Penn, opposed boycotts and stood in the way of their colony’s participation in the Continental Congress. Although John Dickinson, the renowned author of “Letters from a Pennsylvania Farmer to the Inhabitants of the British Colonies,” also opposed boycotts, he was a moderate patriot who supported the idea of a Continental Congress.

Radical politicians such as Joseph Reed, Thomas Mifflin, and Charles Thomson collaborated with Dickinson to overcome conservative opposition. Through their efforts, they persuaded Penn to convene the full legislature to discuss threatened hostilities from Native Americans. Once the legislature was in session, a motion to participate in the Continental Congress was introduced and passed.

In New York, conservative and moderate merchants opposed a boycott but felt it necessary to support the people of Massachusetts Bay. At Fraunces Tavern in New York City, Isaac Low chaired a committee of 51 moderates, radicals, and conservatives that approved the colony’s participation in the Continental Congress.

Massachusetts Bay: Defiance, Deception, and Intrigue

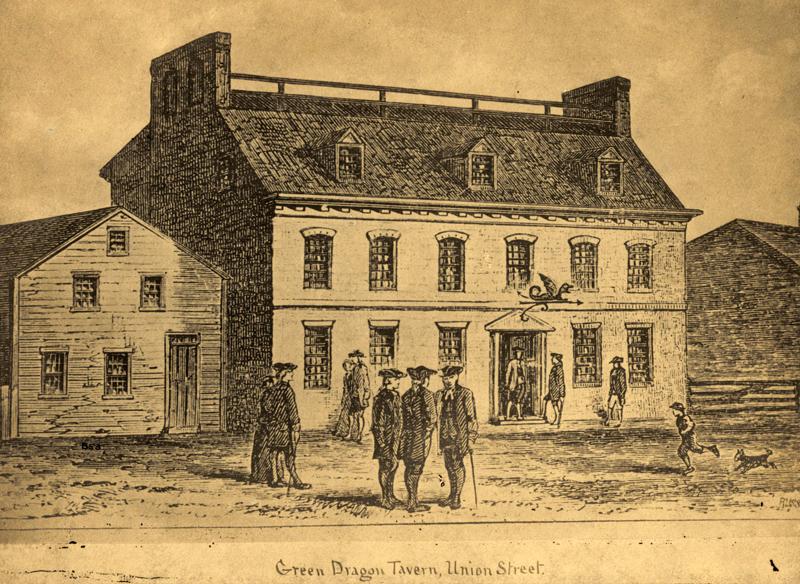

Massachusetts Bay’s legislative body, the General Court, convened in Salem on June 7, 1774. The House of Representatives formed a special committee to address the Port Bill, chaired by Samuel Adams. All committee members were radical patriots, except for the conservative loyalist Daniel Leonard, an attorney from Taunton. Concerned that Leonard might report their activities and intentions to Gage, leading to the dissolution of the General Court, the committee feigned moderation in his presence and discussed reimbursing the costs of the destroyed tea. After Leonard left for the day, the remaining members secretly reconvened to plan for the Continental Congress.To ensure the measure’s approval without Gage’s knowledge, they needed to remove Leonard on the day of the vote. Robert Treat Paine, a radical patriot and friend of Leonard, suggested they both attend court sessions in Taunton. Leonard agreed, unaware that an important vote would take place during his absence. With Leonard gone, the committee approved the measure, which was then brought before the full House.

On June 17, the House met to vote on the resolution to participate in the Continental Congress and to elect its delegates. Conservative loyalists attempted to leave the proceedings to inform Gage, who had taken up residence in Danvers, just outside of Salem. However, Samuel Adams, Dr. Joseph Warren, and the Sons of Liberty anticipated this and had locked all the doors to the House chamber. One conservative loyalist feigned illness, was allowed to leave, and ran directly to Gage’s headquarters. Upon learning of the House’s activities, Gage ordered his secretary, Thomas Flucker (whose daughter was married to Henry Knox), to deliver an official proclamation dissolving the General Court.

Flucker arrived outside the House chamber but found the doors locked. He sent a messenger to inform the speaker that he must be allowed inside. When the speaker denied his request, Flucker began shouting Gage’s proclamation through the locked doors, concluding with the words, “God save the King.”

The Stage Was Set

The Continental Congress was set to convene on Sept. 5, 1774, at Carpenters’ Hall in Philadelphia. The planned historic gathering was not intended to seek independence but to demonstrate the unity of the American colonies in demanding the repeal of the Coercive Acts—referred to by the colonists as the Intolerable Acts. The consensus was that once their demands were met, peace and harmony would be restored between Britain and the colonies.However, with radicals advocating for boycotts, and moderates and conservatives favoring more diplomatic methods, the 56 chosen delegates needed to resolve their differences and agree on a unified approach before presenting their demands to London.

Before the delegates departed for Philadelphia, news of additional punitive measures added to the Coercive Acts reached the colonies. This convinced most Americans that Parliament intended to subjugate the people of Massachusetts Bay as they would a foreign enemy, leading many moderates to align with the radicals.

What arts and culture topics would you like us to cover? Please email ideas or feedback to [email protected]